Share what you know,

and discover more.

Share what you know,

and discover more.

Mar 03, 2022

-

- Charmaine Bantugan

Alcoholism Center for Women

Story Overview: In the fall of 1974, Brenda Weathers and a cadre of lesbian activists and service providers from the Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBT Center) walked up to the sagging porch of 1147 S. Alvarado St. Within the deteriorating ten-bedroom, two and a half story Tudor Revival home in Pico Union, they founded a groundbreaking program – an alcohol rehabilitation center and community space specifically for women and lesbians. Soon, with plants hanging by macrame rope to enliven spaces, parlors and bedrooms are now offices and community rooms. Next door at 1135 S. Alvarado, staff scrubbed grease from the kitchen floor and rearranged furniture in the recovery home. The formation of Alcoholism Center for Women (ACW) in 1975 marked an important shift in Los Angeles’ gay liberation movement, as the rise of street-based activist groups in the 1960s gave way to an institutionalization of quasi-public spaces in the 1970s dedicated to improving LGBTQ+ peoples’ material and metaphysical wellbeing. The two houses offered women, largely lesbians, an array of programming to support sobriety as well as social events to combat social marginalization and foster community. In the 1980s ACW began a pioneering program led by and for Black and Latina women. In 1987, 1147 and 1135 S Alvardo St. were threatened by demolition to make way for a mini-mall. ACW initiated a grassroots campaign that drew in major political leaders like Elizabeth Snyder and Maxine Waters, as well as preservation organizations like the L.A. Conservancy, to nominate the buildings as Historic-Cultural Monuments (HCMs) The buildings were designated for their architectural significance and with support from the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA/LA), ACW bought and rehabilitated the properties. ACW continues its mission to serve marginalized women and care for the buildings. Current clients, like those for the last fifty years, help maintain the grounds and home as part of their recovery process. Conservation is an ongoing and reciprocal relationship of care between the buildings and the women they shelter. History: 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado were constructed respectively in 1907 and 1906 in the Palm Palace Tract of Pico Union as one of the last subdivisions in Pico Union. The development of Pico-Union began in the 1880s as an early suburb for wealthy, white Angelinos that was connected to downtown by railway. In the postwar period, eastern Europe immigrants, displaced elderly, low-income and queer residents from Bunker Hill, then Central America and Mexico immigrants and refugees filled into the neighborhood. Beginning in 1941, 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado were converted into sanitariums or convalescent homes, which operated until the early 1970s. On the Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List, 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado are respectively named August Winstel Residence and Thomas Potter Residences for their original owners. Pico Union and Westlake were a hub for LGBTQ organizing in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Brenda Weathers was an active member of the Gay Liberation Front, which formed the foundation for the Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBTQ Center), founded in 1971 in Westlake. The need for services to treat substance use was a major concern for LGTBQ organizers service providers. In 1973, Brenda Weathers and Lilene Fifield, a social worker at USC, teamed up to write a grant for the Gay Community Services Center for an alcohol rehabilitation program specifically for women and lesbians. Fifield was the author of a groundbreaking study exposing the high rates of substance use in the LGBTQ community and LGBTQ peoples’ exclusion from mainstream treatment programs, and Weathers had the lived experienced to prove it. Due to a conflict over funding that revealed underlying sexism within the male-dominated GCSC, ACW broke from the organization and established themselves as a separate entity at 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado in 1975. ACW has undergone many rehabilitations, both formal and informal, over the decades. The initial rehabilitation began in 1974 with ACW staff who cleaned and revitalized the buildings for their new life as a recovery center. This first act of conservation for the buildings set off a chain of future acts that continue into the present. The formal designation and rehabilitation in 1987 reveal the growing momentum of neighborhood-based preservation efforts and the role of the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA/LA) in advancing community development through historic resources. Significance: The 1970s were an explosive decade for the gay liberation movement that brought the existence, and needs, of gay and lesbian people into greater public consciousness than ever before. The Gay Community Services Center, the first LGBTQ+ drop-in health center in the United States, marked a momentous step towards queer visibility and social service provision. It spawned a number of other programs including the Van Ness Recovery House and the Liberation Houses that integrated social services, public health, in supportive community center and home environments. AWC also emerged at a pivotal moment in the history of public health. In 1965, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) formally adopted the “disease model” of alcoholism, which recognized substance use as medical condition rather than a moral failing. Eight years later in 1973, the APA finally removed homosexuality from the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). ACW stands as physical evidence of the ways women and queer people refused medical institutions that pathologized their ways of being and instead forged new sites that accounted for the physiological, psychological, and social dimensions of health. The founding of ACW, wrote the Lesbian Tide, was the realization of a dream for “an autonomous center run by and for women” that provided an alternative to alcohol as “the unquestioned strategy for survival.” ACW recognized that some of the best people to help women seeking recovery were those who had themselves been through that process. The twenty-three initial staff members were all women, mostly lesbians, and about half self-identified recovering alcoholics. ACW’s programming model advanced their mission of helping women understand their value and exert agency over their lives. In the 1980s, ACW began offering programming for Black and Latina women as well as programming for victims of domestic violence, incest, and people impacted by HIV/AIDS. With programming offered on a sliding scale, they used an intersectional lens to address the root of substance use. ACW’s ethos of care offers guidance to conservationists for methodologies that acknowledge the work of ongoing maintenance, that frame rehabilitation and interpretation around their resonance with current community members, and that view conservation as a transformative act that shapes both people and places.

Alcoholism Center for Women

Story Overview: In the fall of 1974, Brenda Weathers and a cadre of lesbian activists and service providers from the Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBT Center) walked up to the sagging porch of 1147 S. Alvarado St. Within the deteriorating ten-bedroom, two and a half story Tudor Revival home in Pico Union, they founded a groundbreaking program – an alcohol rehabilitation center and community space specifically for women and lesbians. Soon, with plants hanging by macrame rope to enliven spaces, parlors and bedrooms are now offices and community rooms. Next door at 1135 S. Alvarado, staff scrubbed grease from the kitchen floor and rearranged furniture in the recovery home. The formation of Alcoholism Center for Women (ACW) in 1975 marked an important shift in Los Angeles’ gay liberation movement, as the rise of street-based activist groups in the 1960s gave way to an institutionalization of quasi-public spaces in the 1970s dedicated to improving LGBTQ+ peoples’ material and metaphysical wellbeing. The two houses offered women, largely lesbians, an array of programming to support sobriety as well as social events to combat social marginalization and foster community. In the 1980s ACW began a pioneering program led by and for Black and Latina women. In 1987, 1147 and 1135 S Alvardo St. were threatened by demolition to make way for a mini-mall. ACW initiated a grassroots campaign that drew in major political leaders like Elizabeth Snyder and Maxine Waters, as well as preservation organizations like the L.A. Conservancy, to nominate the buildings as Historic-Cultural Monuments (HCMs) The buildings were designated for their architectural significance and with support from the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA/LA), ACW bought and rehabilitated the properties. ACW continues its mission to serve marginalized women and care for the buildings. Current clients, like those for the last fifty years, help maintain the grounds and home as part of their recovery process. Conservation is an ongoing and reciprocal relationship of care between the buildings and the women they shelter. History: 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado were constructed respectively in 1907 and 1906 in the Palm Palace Tract of Pico Union as one of the last subdivisions in Pico Union. The development of Pico-Union began in the 1880s as an early suburb for wealthy, white Angelinos that was connected to downtown by railway. In the postwar period, eastern Europe immigrants, displaced elderly, low-income and queer residents from Bunker Hill, then Central America and Mexico immigrants and refugees filled into the neighborhood. Beginning in 1941, 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado were converted into sanitariums or convalescent homes, which operated until the early 1970s. On the Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List, 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado are respectively named August Winstel Residence and Thomas Potter Residences for their original owners. Pico Union and Westlake were a hub for LGBTQ organizing in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Brenda Weathers was an active member of the Gay Liberation Front, which formed the foundation for the Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBTQ Center), founded in 1971 in Westlake. The need for services to treat substance use was a major concern for LGTBQ organizers service providers. In 1973, Brenda Weathers and Lilene Fifield, a social worker at USC, teamed up to write a grant for the Gay Community Services Center for an alcohol rehabilitation program specifically for women and lesbians. Fifield was the author of a groundbreaking study exposing the high rates of substance use in the LGBTQ community and LGBTQ peoples’ exclusion from mainstream treatment programs, and Weathers had the lived experienced to prove it. Due to a conflict over funding that revealed underlying sexism within the male-dominated GCSC, ACW broke from the organization and established themselves as a separate entity at 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado in 1975. ACW has undergone many rehabilitations, both formal and informal, over the decades. The initial rehabilitation began in 1974 with ACW staff who cleaned and revitalized the buildings for their new life as a recovery center. This first act of conservation for the buildings set off a chain of future acts that continue into the present. The formal designation and rehabilitation in 1987 reveal the growing momentum of neighborhood-based preservation efforts and the role of the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA/LA) in advancing community development through historic resources. Significance: The 1970s were an explosive decade for the gay liberation movement that brought the existence, and needs, of gay and lesbian people into greater public consciousness than ever before. The Gay Community Services Center, the first LGBTQ+ drop-in health center in the United States, marked a momentous step towards queer visibility and social service provision. It spawned a number of other programs including the Van Ness Recovery House and the Liberation Houses that integrated social services, public health, in supportive community center and home environments. AWC also emerged at a pivotal moment in the history of public health. In 1965, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) formally adopted the “disease model” of alcoholism, which recognized substance use as medical condition rather than a moral failing. Eight years later in 1973, the APA finally removed homosexuality from the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). ACW stands as physical evidence of the ways women and queer people refused medical institutions that pathologized their ways of being and instead forged new sites that accounted for the physiological, psychological, and social dimensions of health. The founding of ACW, wrote the Lesbian Tide, was the realization of a dream for “an autonomous center run by and for women” that provided an alternative to alcohol as “the unquestioned strategy for survival.” ACW recognized that some of the best people to help women seeking recovery were those who had themselves been through that process. The twenty-three initial staff members were all women, mostly lesbians, and about half self-identified recovering alcoholics. ACW’s programming model advanced their mission of helping women understand their value and exert agency over their lives. In the 1980s, ACW began offering programming for Black and Latina women as well as programming for victims of domestic violence, incest, and people impacted by HIV/AIDS. With programming offered on a sliding scale, they used an intersectional lens to address the root of substance use. ACW’s ethos of care offers guidance to conservationists for methodologies that acknowledge the work of ongoing maintenance, that frame rehabilitation and interpretation around their resonance with current community members, and that view conservation as a transformative act that shapes both people and places.

Mar 03, 2022

Alcoholism Center for Women

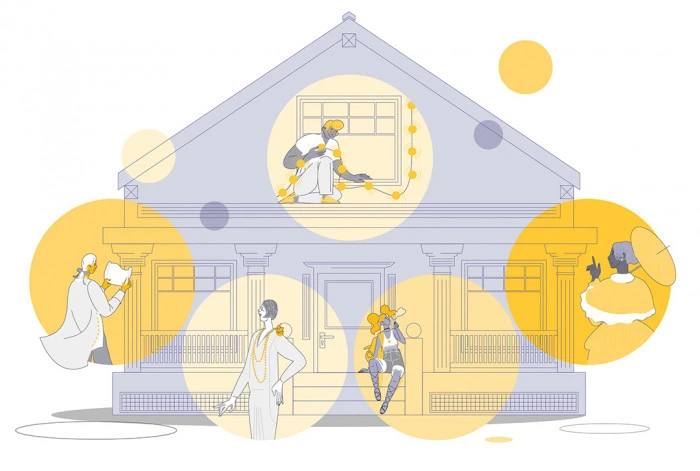

Story Overview:In the fall of 1974, Brenda Weathers and a cadre of lesbian activists and service providers from the Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBT Center) walked up to the sagging porch of 1147 S. Alvarado St. Within the deteriorating ten-bedroom, two and a half story Tudor Revival home in Pico Union, they founded a groundbreaking program – an alcohol rehabilitation center and community space specifically for women and lesbians. Soon, with plants hanging by macrame rope to enliven spaces, parlors and bedrooms are now offices and community rooms. Next door at 1135 S. Alvarado, staff scrubbed grease from the kitchen floor and rearranged furniture in the recovery home.

The formation of Alcoholism Center for Women (ACW) in 1975 marked an important shift in Los Angeles’ gay liberation movement, as the rise of street-based activist groups in the 1960s gave way to an institutionalization of quasi-public spaces in the 1970s dedicated to improving LGBTQ+ peoples’ material and metaphysical wellbeing. The two houses offered women, largely lesbians, an array of programming to support sobriety as well as social events to combat social marginalization and foster community. In the 1980s ACW began a pioneering program led by and for Black and Latina women.

In 1987, 1147 and 1135 S Alvardo St. were threatened by demolition to make way for a mini-mall. ACW initiated a grassroots campaign that drew in major political leaders like Elizabeth Snyder and Maxine Waters, as well as preservation organizations like the L.A. Conservancy, to nominate the buildings as Historic-Cultural Monuments (HCMs) The buildings were designated for their architectural significance and with support from the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA/LA), ACW bought and rehabilitated the properties.

ACW continues its mission to serve marginalized women and care for the buildings. Current clients, like those for the last fifty years, help maintain the grounds and home as part of their recovery process. Conservation is an ongoing and reciprocal relationship of care between the buildings and the women they shelter.

History:

1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado were constructed respectively in 1907 and 1906 in the Palm Palace Tract of Pico Union as one of the last subdivisions in Pico Union. The development of Pico-Union began in the 1880s as an early suburb for wealthy, white Angelinos that was connected to downtown by railway. In the postwar period, eastern Europe immigrants, displaced elderly, low-income and queer residents from Bunker Hill, then Central America and Mexico immigrants and refugees filled into the neighborhood. Beginning in 1941, 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado were converted into sanitariums or convalescent homes, which operated until the early 1970s. On the Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List, 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado are respectively named August Winstel Residence and Thomas Potter Residences for their original owners.

Pico Union and Westlake were a hub for LGBTQ organizing in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Brenda Weathers was an active member of the Gay Liberation Front, which formed the foundation for the Gay Community Services Center (now the LGBTQ Center), founded in 1971 in Westlake.

The need for services to treat substance use was a major concern for LGTBQ organizers service providers. In 1973, Brenda Weathers and Lilene Fifield, a social worker at USC, teamed up to write a grant for the Gay Community Services Center for an alcohol rehabilitation program specifically for women and lesbians. Fifield was the author of a groundbreaking study exposing the high rates of substance use in the LGBTQ community and LGBTQ peoples’ exclusion from mainstream treatment programs, and Weathers had the lived experienced to prove it. Due to a conflict over funding that revealed underlying sexism within the male-dominated GCSC, ACW broke from the organization and established themselves as a separate entity at 1147 and 1135 S. Alvarado in 1975.

ACW has undergone many rehabilitations, both formal and informal, over the decades. The initial rehabilitation began in 1974 with ACW staff who cleaned and revitalized the buildings for their new life as a recovery center. This first act of conservation for the buildings set off a chain of future acts that continue into the present. The formal designation and rehabilitation in 1987 reveal the growing momentum of neighborhood-based preservation efforts and the role of the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA/LA) in advancing community development through historic resources.

Significance:

The 1970s were an explosive decade for the gay liberation movement that brought the existence, and needs, of gay and lesbian people into greater public consciousness than ever before. The Gay Community Services Center, the first LGBTQ+ drop-in health center in the United States, marked a momentous step towards queer visibility and social service provision. It spawned a number of other programs including the Van Ness Recovery House and the Liberation Houses that integrated social services, public health, in supportive community center and home environments.

AWC also emerged at a pivotal moment in the history of public health. In 1965, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) formally adopted the “disease model” of alcoholism, which recognized substance use as medical condition rather than a moral failing. Eight years later in 1973, the APA finally removed homosexuality from the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). ACW stands as physical evidence of the ways women and queer people refused medical institutions that pathologized their ways of being and instead forged new sites that accounted for the physiological, psychological, and social dimensions of health.

The founding of ACW, wrote the Lesbian Tide, was the realization of a dream for “an autonomous center run by and for women” that provided an alternative to alcohol as “the unquestioned strategy for survival.” ACW recognized that some of the best people to help women seeking recovery were those who had themselves been through that process. The twenty-three initial staff members were all women, mostly lesbians, and about half self-identified recovering alcoholics. ACW’s programming model advanced their mission of helping women understand their value and exert agency over their lives. In the 1980s, ACW began offering programming for Black and Latina women as well as programming for victims of domestic violence, incest, and people impacted by HIV/AIDS. With programming offered on a sliding scale, they used an intersectional lens to address the root of substance use.

ACW’s ethos of care offers guidance to conservationists for methodologies that acknowledge the work of ongoing maintenance, that frame rehabilitation and interpretation around their resonance with current community members, and that view conservation as a transformative act that shapes both people and places.

Posted Date

Mar 02, 2022

Historical Record Date

Mar 03, 2022

Source Name

Los Angeles Conservancy

Delete Story

Are you sure you want to delete this story?

Aug 27, 1987

Aug 27, 1987

Mini-Mall vs History

The article titled, "Mini-Malls vs. History" details how the home was almost demolished to make way for a mini-mall at the end of the 1980s.

Delete Story

Are you sure you want to delete this story?

Oct 13, 1942

Oct 13, 1942

Delete Story

Are you sure you want to delete this story?

May 19, 1942

May 19, 1942

Delete Story

Are you sure you want to delete this story?

Dec 12, 1929

To Let - Rooms and Board

Advertisement for rooms for rent at 1135 S. Alvarado in Dec 1925 and 1929. The building was called the "Dixie Lodge".

Dec 12, 1929

Delete Story

Are you sure you want to delete this story?

Apr 01, 1925

Apr 01, 1925

Delete Story

Are you sure you want to delete this story?

Mar 06, 1906

-

- Marley Zielike

Alvarado Street Home

In 1906, an announcement was made for the construction of a new home designed by the renowned architectural firm Hudson & Munsell, commissioned by Thomas McD. Potter. The project, with an estimated cost of $8,285, broke ground on March 6, 1906, with a completion target of just four months. The two-story residence, featuring 10 spacious rooms and a cellar, was set to be a remarkable addition to the area, showcasing elegant design and craftsmanship.

Alvarado Street Home

In 1906, an announcement was made for the construction of a new home designed by the renowned architectural firm Hudson & Munsell, commissioned by Thomas McD. Potter. The project, with an estimated cost of $8,285, broke ground on March 6, 1906, with a completion target of just four months. The two-story residence, featuring 10 spacious rooms and a cellar, was set to be a remarkable addition to the area, showcasing elegant design and craftsmanship.

Mar 06, 1906

Alvarado Street Home

In 1906, an announcement was made for the construction of a new home designed by the renowned architectural firm Hudson & Munsell, commissioned by Thomas McD. Potter.The project, with an estimated cost of $8,285, broke ground on March 6, 1906, with a completion target of just four months. The two-story residence, featuring 10 spacious rooms and a cellar, was set to be a remarkable addition to the area, showcasing elegant design and craftsmanship.

Posted Date

Sep 10, 2024

Historical Record Date

Mar 06, 1906

Source Name

Los Angeles Evening Express

Delete Story

Are you sure you want to delete this story?